|

Click here to buy or sell sports and concert tickets

Part Two - The History of Women's Bodybuilding - by Elsie Huxtable Part Two - The History of Women's Bodybuilding - by Elsie Huxtable

Click here to run the Oakland Baseball Simworld by SBS

Click here to learn about Sports Business Simulations

If you have any questions contact SBS at info@sportsbusinesssims.com

Elsie Huxtable is currently a student at the University of Oregon, and amateur bodybuilder. SBS asked Elsie for permission to use her paper on the history of women's bodybuilding as the basis for a different kind of Internet article a cross between a Blog and Wikipedia. This one permits readers to add to the content by typing comments in designated areas. Thus, anyone can add new information -- or clarify existing information. I hope you enjoy this new format. - Zennie Abraham, Chairman and CEO.

CONT'D -- Nevertheless, by the late seventies, women of all types were beginning to get involved. During the same year, after Snyder's show, a new bodybuilder, Lisa Lyon, stepped onstage and won the Women's World Bodybuilding Championship. Lyon had smoother muscles and a well-balanced body with great symmetry. She had a more athletic and fit look in contrast to the women at Snyder's show. In this way, her physique was a step ahead of Snyder altogether.

|

| Lisa Lyon in Black

|

Lyon's idea of the female physique was parallel to the current trend of feminism. "It's redefining the whole idea of femininity. You don't have to be soft' you don't have to be weak. You can be strong, you can be muscular -- you can make that visual statement and at the same time be feminine." Having early women bodybuilders like Lisa in the picture provoked a fear of what might happen if women could successfully edge out the men in both size and strength. Even some of the women were nervous about the new reality they were creating in bodybuilding. Society at the time was not prepared to see women engage unreservedly in bodybuilding.

Nevertheless, in the early 1980s, they were beginning to do just that. The media soon began to focus on women's bodybuilding with intent curiosity. The Miss Olympia contests began in 1980 and have continued under the International Federation of Bodybuilders ever since.

|

| Rachel McLish

|

In a personal interview with bodybuilding promoter Terry Shipman, he explained that by 1981, you needed a Ms. Olympia to make shows successful and sell tickets. Television covered the first Miss Olympia contest and its winner, Rachel McLish. Rachel, like Lisa Lyon, presented a thinner physique, but later was criticized for having "stringy" muscles. Women's bodybuilding took flips and dives during the 80s, as more and more women entered the Miss Olympia and other national contests of similar federations. Bodybuilding was now regularly portrayed on television and in magazines, but society still wasn't willing to acknowledge women's bodybuilding as a true sport.

Bodybuilding soon split in the 1990s, when women's goals in the sport split down the middle. Some were hardcore bodybuilders who pursued mass and definition. Yet, there were others who took a different route in the sport. Debbie Kruck was one of them. She believed some women lacked the right genetics to compete in the Olympia and in 1995 sponsored the Fitness Olympia. This new addition to the Olympia gave women an opportunity to compete with both muscle and gymnastic skill.

|

| Debbie Kruck

|

The Fitness Olympia included a high heel posing round, gymnastics and fitness routine, and the combination of skill, strength, and muscle. Society's skeptics were content to accept this new addition since it featured women with enough muscle to be competitors, but with the same womanly qualities they admired. At the same time, other critics saw Fitness as a "toned-down" version of real bodybuilding with an added routine.

Figure was a new division that was almost a throw-back to women's bodybuilding contests of the seventies. The contestants did not perform a routine, nor were their physiques incredibly muscular as in a bodybuilder's contests. Bodybuilding promoter, Terry Shipman, admitted that Figure shouldn't be included as a real event. The Fitness Olympia and Figure contests continue today, but some spectators and promoters do not consider them a true component of bodybuilding.

Bodybuilding today still struggles with many of the same issues that seemed unique to the seventies and eighties. Female bodybuilding fought to become a sport in its own right and compete with the same dignity and honor that typical male bodybuilder would possess. Today, this fight continues with some very similar dilemmas.

Society's fear of muscular women, and similarly, women's own fear of being muscular, have been present forever, and is still in the modern world of fitness. Fitness enthusiast and author Karen Andes offers that, "many of us are still afraid of who we might alienate if we get too strong, and simultaneously afraid of the dark, dangerous fates that await us if we don't get strong enough."

The fear of female strength is rampant. Society has always valued male strength in every aspect - aesthetically, physically, and mentally. Female strength was valued, "only when the economy needed it - during wars, when men were away, or when pioneering new lands." In sports, male strength was almost threatened when women wanted to play. Many were and are unwilling to acknowledge what might change if women could compete equally with men. "Size, muscle, power, and the courage to pit body against body in sport were all male with a capital 'M'," and few are willing to let women in on the fun. Even when bigger, more muscular women were beginning to be accepted , some still held the view of "the weaker sex." Peter Neff, a natural bodybuilder stated that women do not have the strength required to control heavy weights and that they risk more injury.

Expectations of women were and still are very different than for men. Physically, women are segregated from men by society's views on what they want for themselves. It is a common idea that women's "problem areas" are their bust, waist, glutes, and thighs. These are seen as the most important and slaved over body parts for women, but only when it comes to losing fat. There is little, if any, notion among society that women might want to build up those same body parts and create a muscular lower body. Men, however, are expected to do the exact opposite in fitness. Their goals are to create a massive chest with strong arms and back. The "muscular" goal is saved only for men. Society, "has women experiencing their bodies in ways that make men comfortable" instead of what they wish to look or act like. Even today, women's bodies are not their own when it comes to physical strength and aesthetic "beauty."

The Changing Female Form

The female form has experienced rapid change since women's bodybuilding first began in the seventies. Aesthetically, women were smaller and used weights to develop their bodies to the point where they were slightly more muscular than gymnasts. In the seventies, women like Rachel McLish were the favorites. They were thinner with more stringy muscles and this seemed to be the accepted image of female bodybuilding. Towards and into the eighties, some women went a step beyond that. These pioneers focused only on muscle and wanted female bodybuilding to grow on that principle.

One of these women, Bev Francis, was an Australian power lifter in the eighties and soon burst through the bodybuilding world at the Caesar World Cup for women in 1983. Her physique was the most muscular that ever graced the bodybuilding stage. She believes that women "should be equal in their opportunities to develop their best aspects, and my best aspect is my strength and my muscularity." This idea caught on to many women of the time, and is still evident in many of the female contest winners of today.

` The stereotype of the thinner, "toned" female still exists in the bodybuilding world today. Since the seventies, the idea female form in fitness was athletic, but trim. Her body must be "supple and definitely toned" and that muscle mass should add to the "natural" female figure rather than detract from it. Proportionality and symmetry are the most important, where the lower and upper body are equal in size and muscle development.

|

| The Buffed Bev Francis

|

This "natural" female figure is also softer, with more body fat and less striations than most male bodybuilders would strive for. Yet, this physique is not ideal for any bodybuilder, who fights fat and soft muscles to an unusual extent. Such stereotypes have continued since the beginning of women's fitness. Some have escaped the darkness and narrow thinking of society, but many have not. Even today, the female form is continually striving for equality as it attempts to break away from these stereotypes.

Current trends in female bodybuilding have held fast since the first women's show in the late seventies. More than anything, the sexual idea portrayed in the sport is obvious. Sex and sensuality play an important role in shaping a female bodybuilder's career and the way she is depicted in the media.

By "fetishizing women's bodies and by making them the objects of heterosexual desire" , they are no longer athletes striving to win, but instead have become the eye candy for the male population's enjoyment. If a female bodybuilder does not appeal to the masses, and most importantly, the male, she has indirectly lost not only a contest, but also her image as an athlete. In one particular magazine, Flex, pictorials are published of women bodybuilders, which on the surface seems an ideal way to promote their image and breakthrough in bodybuilding. Yet, Flex included this statement about the women in the pictorial of Power and Sizzle:

"When photographed in competition shapeÉthey appear shredded, vascular, and hard, and they can be perceived as threatening. Off season they carry more body fat, presenting themselves in a much more naturally attractive conditionÉFlex has been presenting pictorials of female competitors in softer condition. We hope this approach dispels the myth of female bodybuilder masculinity and proves what role models they truly are."

( Read IFBB Pro Nancy Lewis' Letter of Protest to the IFBB regarding unfavorable articles written by male bodybuilders about female bodybuilders in magazines like Flex, with a click here.)

The obvious deduction that hard, ripped, and vascular women are not attractive enough to feature in magazines boosts highlights the issue of sex appeal. Men featured in Flex all have the size and vascularity demanded to be considered in contest shape. Veins bulge from their arms and the word Frankenstein often comes to mind, which can hardly be said for Flex's women. Instead, the beauty queen image still remains on its cover. The danger of these images is that women cannot be seen for being the best athlete they can be, but instead, how sexually attractive they can be to others.

A sexual image is often a feminine one in women's bodybuilding. Femininity is no new concept, and certainly not one anyone could decide upon since the first women's bodybuilding show in the late seventies. The first feminine woman was one who had softness and curves, with muscle distributed sparingly on her body. By the time Lisa Lyon stepped onstage, the ideal "feminine" physique had some added muscle, yet still did not have the same emphasis on building it up. Lynn Conkwright offered that, "Muscles have their place - on stage. But never too many. Some women carry it too farÉwe don't. We want to be women - we want the muscularity to enhance our femininity."

Yet, even when femininity was so important, both to judges, coaches, and competitors, there wasn't a set definition on what "feminine" actually was. No one was sure what a "fit" female looked like. As women's bodybuilding in the eighties became more widespread, the idea of femininity changed. Muscle was then considered feminine, but only to a certain degree. If it was taken too far, suddenly the contestant was criticized for being "masculine," as in the case of Bev Francis. Many women walked a fine line between the two. Terry Shipman offered that femininity consisted of a "flowing physique and how they [contestants] carry themselves." Yet, for some of the women competitors, femininity included muscle. Carla Dunlap, winner of the 1983 Caesar World Cup, proposed that she was, "caught up in the fascination of muscular beauty" and saw bodybuilding as a "combination of sport and exhibition." The gray area was widening and more and more women began to take advantage of it. This did not mean, however, that the public was ready to accept their migration.

|

| Carla Dunlap

|

Society's view on femininity provides the staying power for some contestants and determines the end of others. It all comes down to how popular a bodybuilder is with the public and of course, the judges. Off the stage, bodybuilding is in the hands of the masses. Most of them are men. The current trend of femininity by their definition is a woman with enough muscle to be athletic-looking, while retaining her traditional and natural proportions as a woman. Yet, as Al Thomas, a writer and advocate for female muscle points out, "Muscles have been admired in all of God's creatures but one the human female." Certainly, if women are considered feminine beings and judged so by society, muscle must play little, if any role in their athletic look. The definition of femininity is almost impossible to change for women bodybuilders themselves. It is in the hands of the judges and the public as to who makes the "feminine" cut.

The idea of femininity today governs female bodybuilding, and is rarely the other way around. Many are of the opinion that without femininity in contests, female bodybuilding would ultimately fail as a sport. Without support from the public, shows could never raise enough money to continue publicizing them. If women abandoned the feminine ideal altogether, promoters claim, there would be no money in the sport of women's bodybuilding. No one would want to pay to see women go against the accepted view of the "feminine physique." Americans are not agreeable with large musculature on women and most men feel threatened by it. The fear of how far women might go in the sport would ultimately drive away its audience, since, "womanly muscularity is a badge of vigor in a society that still too often prefers its women of a doughier consistencyÉ" Female bodybuilding would be dead.

Muscle and Feminity: Mutually Exclusive?

Critics conclude that muscles and femininity are at odds with each other as female bodybuilding grows into the modern world of sports. The feminine ideal persists with much vigor and is preferred to maximum muscle in any contest, and on any cover of any magazine. In his book, Natural Bodybuilding for Men and Women, Peter Neff comments on this ideal. The female physique ought to be athletic and trim, "supple and definitely toned." The ideal woman should have body fat levels between fifteen and twenty percent. If a woman were to dip below fifteen percent, she would definitely lose her feminine shape and be too muscular. Proportion and symmetry are key for the ideal female physique. Muscle is not the standard, instead it is optimal for women to retain their "feminine" quality. For those like Neff, women's bodybuilding is less about muscles, and more about sensuality. Attempting to combine the two, calls for dangerous chemistry in the world of female bodybuilding.

Femininity applies not only in society's view of women, but also in the judging of these same female contestants. The "feminine rule" is as vague onstage as it is off, but is nevertheless, imperative in the deciding vote. Femininity will make or break it both for pros and amateurs, as well as the judges themselves in deciding who fits these criteria. Often judges attempt to pinpoint what femininity is among themselves before judging a contest. Ironically, their consensus is an understood rule at both the National Physique Committee (NPC) and the International Federation of Bodybuilders (IFBB) sanctioned contests. Judges earn themselves a spot on the panel based on how their judging scores math with current judging scores. Judges are required to look for "muscular femininity" taking into consideration that the women should have "female-looking muscles." The IFBB clearly states its opposition to "male-sized muscles." Without retaining her "feminine" qualities, a woman has little or no chance of winning a contest or title, even when trying to make it to the professional level. Therefore, most women find themselves at an impasse with no other choice but to succumb to judging standards.

Both the NPC and the IFBB organizations are run together under the same management. What is a standard for one is a standard for the other. Both organizations heavily promote favoring feminine women when judging both amateur and pro shows. The guidebook suggests that, "the judge must bear in mind that he or she is judging a woman's bodybuilding competition and is looking for an ideal feminine physiqueÉ" Judges believe that "the most important aspect is shape, a feminine shape, and controlling the development of muscle - it must not be carried to excess, where it resembles the massive muscularity of the male physique." This explains why the "most muscular" pose is not included for women and why poses for women are often restricted. In 1993, the federation lifted its ban on muscles being too big on women. However, the idea of feminine muscle still stands in the judging criteria.

The women's standards in contests differ from men's in order to promote this feminine approach to bodybuilding. Differences pop up everywhere, in all aspects of competition, from the presentation round to the last line-up when the winner is chosen. The most obvious is seen in the official NPC guidebook of rules and regulations. Compulsory rounds for both men and women consist of about six predetermined poses used to evaluate the competitors onstage. Women complete six poses, but are exempt from others deemed too masculine. These include the front lat spread, which shows off chest and total upper body development, and the back lat spread, which focuses on muscles of the upper and middle back as well as total upper body from a rear view. The "Most Muscular" pose is optional for men to perform onstage, but is not included for women. The strikingly obvious difference in the contests is the tendency to favor men in showing off muscles and vascularity in the compulsory round.

|

| "SuperJody" - Jody May shows a front lat spread

|

To allow a woman to make this same statement onstage would go against all judges' regulations and the idea of femininity that the Weider Corporation admits to adhering to. Women's bodybuilding, in this regard, is little more than a beauty contest with the illusion of fitness and strength. In this way, the women's standards truly reflect the ideal femininity that both the organizations wish to promote.

A NPC or IFBB contest will dictate what it considers to be feminine, and therefore appropriate for women competitors, in the procedure of events. During the contest, three imperative criteria are used to judge the winner. All are equal in grading. Presentation rounds display all muscle groups in the women to show "muscular development and aesthetic lines." This round allows the competitor to take direction in presenting their physiques. However, as mentioned above, women are exempt from some of the mandatory poses for male bodybuilders including the front and back alt spreads. The danger of performing these poses is representing a "masculine" physique in the judges' eyes. Doing this would ultimately be a disaster for a woman who was close in competition.

The symmetry of a contestant ties in closely with the value of proportion when judging takes place. For this criterion, an overall view of the women is taken into consideration. Shape and balance are the main focus in judging symmetry. The general assessment round takes symmetry very seriously to ultimately choose a winner. This hurts all women competitors, because the "overall package" focuses heavily on the elusive feminine component. Judges are looking at aesthetic qualities that have little if anything to do with bodybuilding and muscularity. This can also be the difference between being the overall winner and a second place finish.

Muscular Development and Judging

Muscular development is equally important in judging as presentation and symmetry, even more so. This aspect is seen in the next rounds of posing between contestants. Round Two shows off each competitor with flexed muscles as an individual and as a group. Judges refine their former impressions of each athlete in this round. Muscular development is judged on density, separation, and definition. Balance is key for assessing muscular development, since muscle should, ideally be paired with proportion. This is the crux of the dilemma for female bodybuilders. A bodybuilding contest cannot be won without muscles. The same contest can easily be lost with too much. As judges have expressed, they aren't looking for overly muscular women. Feminine is the way to be. Yet, how much muscle will make or break a woman's chances? Apparently, not a whole lot. Since the judges themselves have slightly different views on what constitutes "too much muscle," contestants are at the mercy of each individual judge when it comes to scoring.

The general consensus is that each judge should be looking for "muscular femininity," which causes even more problems for the women onstage. The feminine rule in female bodybuilding contests is a vague and distressing one for every competitor. Judges cannot even agree on the definition of femininity for scoring. The eighties notion of being "one of the guys" but still "looking like a girl" still stands as long as the "feminine rule" does.

The Problem of Judging in Contests

This discord with the definition of femininity leads to inconsistent contest results in professional competitions. Most male contests are clear as to what is desirable and what their goals are between training for shows. Women have had to hit and miss with each contest due to the fickle attitudes of general judging. Oftentimes, the discrepancy lies between two athletes with dissimilar physiques. Such a case is seen with Lenda Murray and Bev Francis during the 1990 Ms. Olympia. Both competitors were close in scores by the end of the first two rounds, but Murray won the contest over a large point difference.

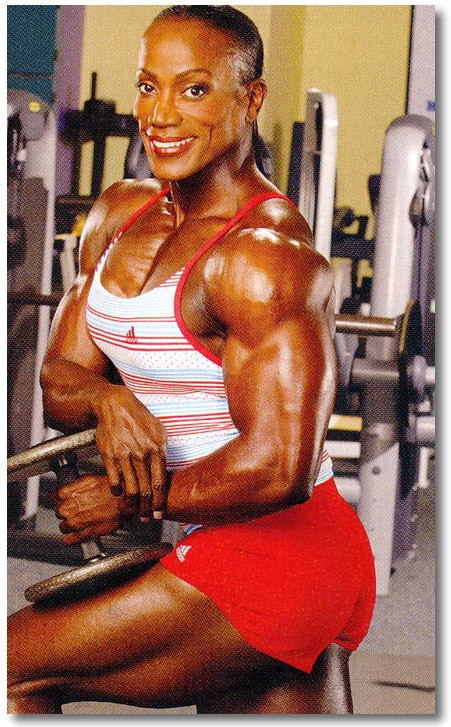

Lenda Murray, the winner of the 1990 Ms. Olympia and a muscular but more feminine and symmetrical bodybuilder, won the contest. Bev Francis placed second. To lose a contest after leading the first two rounds by seven points is a relatively unusual occurrence in pro bodybuilding, especially given the fact that in the latter two rounds, the two competitors were closely matched.

|

| Lenda Murray

|

This inconsistent judging leaves most women in awe over the results of most contests. Bev Francis, one of the most muscular bodybuilders, would always place in a contest, but never win. Judges wanted to make a clear distinction of what was muscular and what was masculine. The catch in this theory, is that it changed from contest to contest, especially in the Ms. Olympia. In the 2000 Ms. Olympia contest, there were actually two winners chosen for the overall title. Valentina Chepiga and Andrulla Blanchette, the first place heavy and lightweight respectively, tied for the overall award. That year, two Ms. Olympias were crowned. The difference in judging was great because no one could distinguish which physique was superior to another, and so there was little choice but to award a tie for their indecision.

|

| Valentina Chepiga

|

Professional bodybuilder, Valentina Chepiga, sums it up after the 2001 Ms. Olympia, "I don't know what the judges want. Last year I was good [in the judges' eyes], now I'm not." Judging and the feminine ideal have never seen eye to eye, and inconsistent scores prove that. The ideal femininity cannot be defined to where it meets the expectations of judges, promoters, and bodybuilders alike.

Want to add to this? Click below...

|

The Feminine Ideal and Women's Bodybuilding

Disproving the feminine ideal is imperative for female bodybuilding to succeed and be recognized. Female bodybuilders since the eighties have tried to approach bodybuilding from their own views, instead of judges' or promoters' "feminine" images. Kay Baxtor, who appeared at the 1982 Ms. Olympia, explained that, "I train for my own satisfactionÉand to be the ultimate female warrior." She also offered that, "I actively seek to go beyond what is asked for at a contest." Many women who take this route understand the indecisive judging that happens in professional contests and choose not to let it apply to them personally as athletes.

Similarly, Carolyn Cheshire was told early in her lifting endeavors, that exercises like curls and shrugs would build ugly, bulgy arms. Abandoning this idea, she later went on to compete in the first Ms. Olympia in 1980. She stated, "I am all for Amazonian size, strength, and super fitness for womenÉ" Most of the women in the eighties had been told at one point in their lives that bodybuilding wouldn't suit them, or that their bodies would become unnatural for their sex. Yet, for most women, when they got a taste of their power in the sport, it became addicting. It seems, in most cases, that femininity has little, if anything to do with the physical woman. Instead, many feel that their femininity is an internal trait that is not repressed by muscularity and strength.

In order to assist in disproving the feminine image for women bodybuilders, the equality of men's and women's physiques must be defined and accepted. If the feminine rule is to be replaced in alternative judging methods, it must be done so with a concept many female bodybuilders have proved onstage and in their goals for creating a desirable physique.

Physiology factors lay heavily into making the need for eliminating the "feminine rule" important in judging. Myths surrounding the female and muscle have made it more and more difficult for women to be accepted as muscular and even favorable to muscle. The connection between masculinity and muscularity plays a large role in feeding these myths. The general idea in society is that women compromised "masculinity" when they developed themselves physically. However, women and men are equal in their abilities to build and carry significant muscularity in proportion to their body frame, hence, muscle is both "feminine" and "masculine.

Natural bodybuilder, Peter Neff, offers the biggest retaliation against equality in muscularity. Women have less muscle tissue and lack enough testosterone to build muscles like men. A woman's biggest challenge is keeping a proportional body, due to a tendency to gain most of her weight in her lower body. His recommendations for weights are to use 10% of a woman's bodyweight doing bench presses and bicep curls, and 20% for squats to build quads. These weights, however, are too light to stimulate muscle fibers, let alone build muscle at all, even if "toning" is the goal. Heavy weights build muscle in men, as well as women. Dowling suggests, more accurately, that, "there is nothing inherently different in the physiological makeup of girls and boys that would account for differences inÉany physical skills."

The notion of men having a greater ability to build muscle both naturally and unnaturally is false, mainly because of their larger natural frame. Full body photographer, Zach Taylor, explains that some bodybuilders on steroids can look no more muscular than some naturals. What it really comes down to is a person's individual boy structure, regardless of sex. It would be absurd to suggest, as Neff did earlier, that women are doomed from the start in creating a natural, quite muscular physique. If both women and men have the ability to build muscle, then muscle is no longer a "masculine" characteristic. Instead, muscular women should be seen every bit as eligible to win a contest. The "feminine rule" plays no part.

Physiology factors, however, can stem from unnatural means as well as natural ones. Steroid use is so common in many professional contests, that the outcome of such use cannot be regarded as "masculine." The IFBB has denied supporting illegal substances like steroids. Testing positive carries a high penalty. The trick is that although most professionally sponsored competitions state that they test contestants, they actually do not.

Rick Wayne, author of Muscle Wars, mentions, "Not one of the musclemen participating in the 1984 IFBB MR. Universe was tested for steroid use. Otherwise it's a safe bet there would have been no contest." Steroid use for men is just as unnatural as it is for women, but women are often penalized for showing signs of steroid use due to the fact that it detracts from their femininity. Women, for instance, are not allowed to have cross-striations since it is an indicator of steroid abuse to some judges.

However, the rules still state that judges cannot deduct points from someone, male or female, for signs of steroid use if the competitor has tested negative. Even so, off the stage, "steroid use" is a much avoided concept when centering on the female physique. Society has condemned the idea of women on steroids and consequently, promoters of shows and editors of magazines stray far from making huge, muscular women the object of interest.

Female Bodybuilders and Steroids

One professional female stated that, "had she been confronted with a 'jocky-looking, gross-looking girl'...she would have tried her hand at another activity besides weight training." The reality, however, is that a majority of female bodybuilders with pro status onstage are using steroids or other illegal substances. Men, of course, are no exception. Zach Taylor, who photographs professional bodybuilders and related physiques, admits that among those he works with that there is a huge grey area where one cannot be sure whether the individual is on steroids or not. What is accepted more often now in the bodybuilding community is that shows will be open and contestants will most likely be on steroids - both women and men. Physiology factors of building muscle, both naturally and unnaturally, are a part of both women's and men's bodybuilding and should be accepted for women.

Women's independence is imperative for bodybuilding if it is to flourish and dominate. The most important goal for female bodybuilding is pursuing the sport equally as the men. The concept of femininity is present only for the women, and hurts them as competitors and individual sportspeople. Judges cannot agree on a winning physique that is the guideline for late contestants to follow. Men know what they need to win, and so should women.

The top male bodybuilder, Ronnie Coleman, is described as having, "some of the freakiest body parts on the planet," a great compliment in the bodybuilding world. Yet, no one would dare describe a woman in such a way, but if she has worked hard enough and is deserving of such regard, she should be. Words associated with women in the sport are sexy, shapely, tight, cut, hard, and feminine. Women ought to be described according to how society describes men: rock-hard, thick, deep cuts, and "mountains of muscle" if they portray such physiques onstage. Female bodybuilding is in dire need to eliminate the "feminine" idea of their strength and size and view it as nothing but their own individual passion for strong bodies.

Female Bodybuilding's New Identity

The feminine rule of female bodybuilding contests hurts all women competitors. The idea female form has evolved over the decades only as far as mainstream society was ready to see it go. Since the first female show in the late 70s, women's physical fitness has been displayed in a way that makes men and general society most comfortable. There has been an accepted ideal body in women's bodybuilding both in promotion and judging of contests. This consists of the femininity factor and the overall package that she presents onstage.

The feminine rule rule hurts female competitors, as they are restricted in how much muscle they can show off in a contest. They are not judged according to their passion for lifting or their ability to display their physique, but instead to gender norms and societal ignorance. Women lifters should be judged independent of any visual femininity, but only on the basis of muscle size, shape, and definition, just as men are. After over two decades of musclewomen onstage, female bodybuilding has taken on a new identity of power and prestige onstage and femininity has nothing to do with it.

...back to start.

Women's Bodybuilding Link References.

Bibliography

Gains, Butler. PumpingIron II: The Unprecedented Woman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984

Weider, Ben and Weider, Joe. The Edge. New York: Penguin, 2002

Andes, Karen. A Woman's Book of Strength. New York: Perigee, 1995

Weider, Joe and Weider, Betty. The Weider Book of Bodybuilding for Women. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1981

Neff, Peter. Natural Bodybuilding for Men and Women. New York: Avion, 1985

Berg, Michael. "Upset at the Ms. Olympia." Muscle & Fitness Feb. 2002

Engel, Kathleen. "Yaxeni Oriquen Outmuscles the Competition." Muscle & Fitness July 2002

NPC News Online. "NPC Rules and Regulations" [Online] 15 Oct. 2002

Available: www.npcnewsonline.com

Heywood, Leslie. Bodymakers. London: Rutgers University Press, 1998

Dowling, Colette. The Frailty Myth. New York: Random House, 2000

Kennedy, Robert and Weider, Ben. Superpump! Hardcore Women's Bodybuilding. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 1986

Lowe, Maria R. Women of Steel. New York: NYU Press, 1998

IFBB News Online. "IFBB Rules" [Online] Nov. 2002

Available: http://www.getbig.com

X-hwang, Gene. "2000 Ms. Olympia and Fitness" [Online] Nov. 2002

Available: www.genex9.com

Shipman, Terry, Personal Interview.22 December, 2002

Taylor, Zach, Personal Interview. 31 January, 2003

McLean Hostipal. "Many Women Bodybuilders Abuse SteroidsÉSuffer from Body Image Disorders" [Online] March 2003

Available: www.mcleanhospital.org/PublicAffairs.html

Everson, Corinna. Cory Everson's Workout. New York: Perigree Books, 1991

Webster, David. Bodybuilding: An Illustrated History. New York: Arco Publishing, 1979

Want to add to this? Click below...

|

|